You can love Shel Silverstein because he was a Renaissance Man, yet a Captain of the Unpretentious—singer-songwriter, screenwriter, playwright, cartoonist, iconic children’s author. You can love him because of his range. He wrote iconic songs like “A Boy Named Sue” (he won a 1970 Grammy) and iconic books like

The Giving Tree. He created illustrated travel journals for

Playboy about everything from a baseball training camp to a nudist colony, from Haight-Ashbury to Fire Island, from Spain to Switzerland (“I’ll give them 15 more minutes, and if nobody yodels, I’m going back to the hotel.”)

You can love him because he said things like this: "When I was a kid… I would much rather have been a good baseball player or a hit with the girls, but I couldn't play ball. I couldn't dance. Luckily, the girls didn't want me. Not much I could do about that. So I started to draw and to write… By the time I got to where I was attracting girls, I was already into work, and it was more important to me. Not that I wouldn't rather make love, but the work has become a habit."

You can love him because he called himself Uncle Shelby, even those his real name was Sheldon. You can love him because he was a survivor. He was a Korean War veteran who espoused peace. He was a poet who made children smile around the world—with illustrated poetry collections like

Where the Sidewalk Ends, A Light in the Attic, Falling Up, and

Every Thing On It—even though he himself lost a daughter to a cerebral aneurysm when she was 11.

It may be that only Dr. Seuss combined whimsy and profundity—imagination and insight—as deftly as Silverstein did. And Silverstein could do it in only a few lines. So we at the

Why Not 100 have chosen our 46 favorite Shel Silverstein mini-masterpieces, starting with the perfect one:

1.

INVITATION (

Where the Sidewalk Ends)

If you are a dreamer, come in,

If you are a dreamer, a wisher, a liar,

A hope-er, a pray-er, a magic bean buyer…

If you’re a pretender, come sit by my fire

For we have some flax-golden tales to spin.

Come in!

Come in!

2.

HOW MANY, HOW MUCH (

A Light in the Attic)

How many slams in an old screen door?

Depends how loud you shut it.

How many slices in a bread?

Depends how thin you cut it.

How much good inside a day?

Depends how good you live ‘em.

How much love inside a friend?

Depends how much you give ‘em.

3.

LISTEN TO THE MUSTN’TS (

Where the Sidewalk Ends)

Listen to the MUSTN’TS, child,

Listen to the DON’TS

Listen to the SHOULDN’TS

The IMPOSSIBLES, the WON’TS

Listen to the NEVER HAVES

Then lost close to me—

Anything can happen, child,

ANYTHING can be.

4.

MASKS (

Every Thing On It)

She had blue skin.

And so did he.

He kept it hid

And so did she.

They searched for blue

Their whole life through,

Then passed right by—

And never knew.

5.

PANCAKE? (

Where the Sidewalk Ends)

Who wants a pancake,

Sweet and piping hot?

Good little Grace looks up and says,

“I’ll take the one on top.”

Who else wants a pancake,

Fresh off the griddle?

Terrible Theresa smiles and says,

“I’ll take the one in the middle.”

6.

SNOWBALL (

Falling Up)

I made myself a snowball

As perfect as could be.

I thought I’d keep it as a pet

And let it sleep with me.

I made it some pajamas

And a pillow for its head.

Then last night it ran away,

But first—it wet the bed.

7.

SOMETHING MISSING (

A Light in the Attic)

I remember I put on my socks,

I remember I put on my shoes.

I remember I put on my tie

That was printed

In beautiful purples and blues.

I remember I put on my coat,

To look perfectly grand at the dance,

Yet I feel there is something

I may have forgot—

What is it? What is it?...

8.

UNDERFACE (

Every Thing On It)

Underneath my outside face

There’s a face that none can see.

A little less smiley,

A little less sure,

But a whole lot more like me.

9.

I WON’T HATCH (

Where the Sidewalk Ends)

Oh I am a chicken who lives in an egg,

But I will not hatch, I will not hatch.

The hens they all cackle, the roosters all beg,

But I will not hatch, I will not hatch.

For I hear all the talk of pollution and war

As the people all shout and the airplanes roar,

So I’m staying in here where it’s safe and it’s warm,

And I WILL NOT HATCH!

10.

PUT SOMETHING IN (

A Light in the Attic)

Draw a crazy picture,

Write a nutty poem,

Sing a mumble-gumble song,

Whistle through your comb.

Do a loony-goony dance

‘Cross the kitchen floor,

Put something silly in the world

That ain’t been there before.

11.

YESEES AND NOEES (

Every Thing On It)

The Yesees said yes to anything

That anyone suggested.

The Noees said no to everything

Unless it was proven and tested.

So the Yesees all died of much too much

And the Noees all died of fright,

But somehow I think the Thinkforyourselfees

All came out all right.

12.

HUG O’WAR (

Where the Sidewalk Ends)

I will not play tug o’ war.

I’d rather play hug o’ war,

Where everyone hugs

Instead of tugs,

Where everyone giggles

And rolls on the rug,

Where everyone kisses,

And everyone grins,

And everyone cuddles,

And everyone wins.

13.

RIDICULOUS ROSE (

Where the Sidewalk Ends)

Her mama said, “Don’t eat with your fingers.”

“OK,” said Ridiculous Rose,

So she ate with her toes.

14.

MONSTERS I’VE MET (

A Light in the Attic)

I met a ghost, but he didn’t want my head,

He only wanted to know the way to Denver.

I met a devil, but he didn’t want my soul,

He only wanted to borrow my bike awhile.

I met a vampire, but he didn’t want my blood,

He only wanted to nickels for a dime.

I keep meeting all the right people—

At all the wrong times.

15.

EARLY BIRD (

Where the Sidewalk Ends)

Oh, if you’re a bird, be an early bird

And catch the worm for your breakfast plate.

If you’re a bird, be an early bird—

But if you’re a worm, sleep late.

16.

JAKE SAYS (

Every Thing On It)Yes, I'm adopted.

My folks were not blessed

With me in the usual way.

But they picked me,

They chose me

From all the rest,

Which is lots more than most kids can say.

17.

COLORS (

Where the Sidewalk Ends)

My skin is kind of sort of brownish

Pinkish yellowish white.

My eyes are grayish blueish green,

But I’m told they look orange in the night.

My hair is reddish blondish brown,

But it’s silver when it’s wet.

And all the colors I am inside

Have not been invented yet.

18.

MAGIC (

Where the Sidewalk Ends)

Sandra’s seen a leprechaun,

Eddie touched a troll,

Laurie danced with witches once,

Charlie found some goblins’ gold.

Donald heard a mermaid sing,

Susy spied an elf,

But all the magic I have known

I’ve had to make myself.

19.

LITTLE PIG’S TREAT (

Falling Up)

Said the pig to his pop,

“There’s the candy shop.

Oh, please let’s go inside.

And I promise I won’t

Make a kid of myself

If you give me a people-back ride.”

20.

FALLING UP (

Falling Up)

I tripped on my shoelace

And I fell up—

Up to the roof tops,

Up over the town,

Up past the tree tops,

Up over the mountains,

Up where the colors

Blend into the sounds.

But it got me so dizzy

When I looked around,

I got sick to my stomach

And I threw down.

21.

FISH? (

Where the Sidewalk Ends)

The little fish eats the tiny fish,

The big fish eats the little fish—

So only the biggest fish gets fat.

Do you know any folks like that?

22.

OURCHESTRA (

Where the Sidewalk Ends)

So you haven’t got a drum, just beat your belly.

So I haven’t got a horn—I’ll play my nose.

So we haven’t any cymbals—

We’ll just slap our hands together,

And though there may be orchestras

That sound a little better

With their fancy shiny instruments

That cost an awful lot—

Hey, we’re making music twice as good

By playing what we’ve got!

23.

MORGAN’S CURSE (

Falling Up)

Followin’ the trail on the old treasure map,

I came to the spot that said, “Dig right here.”

And four feet down my spade struck wood

Just where the map said a chest would appear.

But carved in the side were written these words:

“A curse upon he who disturbs this gold.”

Signed, Morgan the Pirate, Scourge of the Seas.

I read these words and my blood ran cold.

So here I set upon untold wealth

Tryin’ to figure which is worse:

How much do I need this gold?

And how much do I need this curse?

24.

THE EDGE OF THE WORLD (

Where the Sidewalk Ends)

Columbus said the world is round?

Don’t you believe a word of that.

For I’ve been down to the edge of the world,

Sat on the edge where the wild wind whirled,

Peeked over the ledge where the blue smoke curls,

And I can tell you, boys and girls,

The world is FLAT!

25.

THE PLANET OF MARS (

Where the Sidewalk Ends)

On the planet of Mars

They have clothes just like ours,

And they have the same shoes and same laces,

And they have the same charms and same graces,

And they have the same heads and same faces…

But not in the

Very same

Places.

26.

IT’S DARK IN HERE (

Where the Sidewalk Ends)

I am writing these poems

From inside a lion,

And it’s rather dark in here.

So please excuse the handwriting

Which may not be too clear.

But this afternoon by the lion’s cage

I’m afraid I got too near.

And I’m writing these lines

From inside a lion,

And it’s rather dark in here.

27.

COMPLAININ’ JACK (

Falling Up)

This morning my old jack-in-the-box

Popped out—and wouldn’t get back-in-the-box.

He cried, “Hey, there’s a tack-in-the-box,

And it’s cutting me through and through.”

“There also is a crack-in-the-box,

And I never find a smack-in-the-box,

And sometimes I hear a quack-in-the-box,

‘Cause a duck lives in here, too.”

Complain, complain is all he did—

I finally had to close the lid.

28.

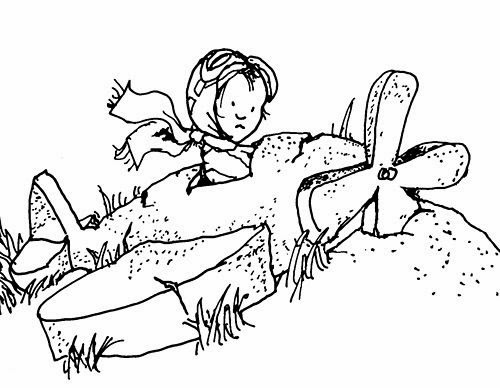

STONE AIRPLANE (

Falling Up)

I made an airplane out of stone…

I always did like staying home.

29.

INVENTION (

Where the Sidewalk Ends)

I’ve done it, I’ve done it!

Guess what I’ve done!

Invented a light that plugs into the sun.

The sun is bright enough,

The bulb is strong enough,

But, oh, there’s only one thing wrong…

The cord ain’t long enough.

30.

WHO (

Where the Sidewalk Ends)

Who can kick a football

From here out to Afghanistan?

I can!

Who fought tigers in the street

While all the policemen ran and hid?

I did!

Who will fly and have X-ray eyes—

And be known as the man no bullet can kill?

I will!

Who can sit and tell lies all night?

I might!

31.

THE FOURTH (

Where the Sidewalk Ends)

Oh

CRASH!

my

BASH!

it’s

BANG

the

ZANG!

Fourth

WHOOSH!

of

BAROOM!

July

WHEW!

32.

I MUST REMEMBER (

Where the Sidewalk Ends)

I must remember…

Turkey on Thanksgiving,

Pudding on Christmas,

Eggs on Easter,

Chicken on Sunday,

Fish on Friday,

Leftovers, Monday,

But ah, me—I’m such a dunce.

I went and ate them all at once.

33.

SCALE (

Falling Up)

If I could only see the scale,

I’m sure that it would state

That I’ve lost ounces… maybe pounds

Or even tons of weight.

“You’d better eat some pancakes—

You’re skinny as a rail.”

I’m sure that’s what the scale would say…

If I could see the scale.

34.

THE ACROBATS (

Where the Sidewalk Ends)

I’ll swing

By my ankles,

She’ll cling

To your knees

As you hang

By your nose

From a high-up

Trapeze.

But just one thing, please,

Don’t sneeze.

35.

A LIGHT IN THE ATTIC (

A Light in the Attic)

There’s a light on in the attic.

Though the house is dark and shuttered,

I can see a flickerin’ flutter,

And I know what it’s about.

There’s a light on in the attic.

I can see it from the outside,

And I know you’re on the inside… lookin’ out.

36.

THE WORST (

Where the Sidewalk Ends)

When singing songs of scariness,

Of bloodiness and hairyness,

I feel obligated at this moment to remind you

Of the most ferocious beat of all:

Three thousand pounds and nine feet tall—

The Glurpy Slurpy Skakagrall—

Who’s standing right behind you.

37.

CRYSTAL BALL (

Falling Up)

Come see your life in my crystal glass—

Twenty-five cents is all you pay.

Let me look into your past—

Here’s what you had for lunch today:

Tuna salad and mashed potatoes,

Green pea soup and apple juice,

Collard greens and stewed tomatoes,

Chocolate milk and lemon mousse.

You admit I’ve told it all?

Well, I know it, I confess,

Not by looking in my ball,

But just by looking at your dress.

38.

HOW NOT TO HAVE TO DRY THE DISHES (

Falling Up)

If you have to dry the dishes

(Such an awful, boring chore)

If you have to dry the dishes

(‘Stead of going to the store)

If you have to dry the dishes

And you drop one on the floor—

Maybe they won’t let you

Dry the dishes anymore.

39.

WARNING (

Where the Sidewalk Ends)

Inside everybody’s nose

There lives a sharp-toothed snail.

So if you stick your finger in,

He may bite off your nail.

Stick it farther up inside,

And he may bite your ring off.

Stick it all the way, and he

May bite the whole darn thing off.

40.

CAPTAIN HOOK (

Where the Sidewalk Ends)

Captain Hook must remember

Not to scratch his toes.

Captain Hook must watch out

And never pick his nose.

Captain Hook must be gentle

When he shakes your hand.

Captain hook must be careful

Openin’ sardine cans

And playing tag and pouring tea

and turnin’ pages of this book.

Lots of folks I’m glad I ain’t—

But mostly Captain Hook!

41.

MY ZOOOTCH (

Every Thing On It)I never have nightmares,

I’m happy to say.

The Zoootch on my bed

Always scares ‘em away.

42.

NOPE (

Falling Up)

I put a piece of cantaloupe

Underneath the microscope,

I saw a million strange things sleepin’,

I sawa zillion weird things creepin’,

I saw some green things twist and bend—

I won’t eat cantaloupe again.

43.

MY RULES (

Where the Sidewalk Ends)

If you want to marry me, here’s what you’ll have to do:

You must learn how to make a perfect chicken-dumpling stew.

And you must sew my holey socks,

And soothe my troubled mind,

And develop the knack for scratching my back,

And keep my shoes spotlessly shined.

And while I rest you must rake up the leaves,

And when it’s hailing and snowing

You must shovel the walk… and be still when I talk,

And—hey—where are you going?

44.

DIVING BOARD (

Falling Up)

You’ve been up on that diving board

Making sure that it’s nice and straight.

You’ve made sure that it’s not too slick.

You’ve made sure it can stand the weight.

You’ve made sure that the spring is tight.

You’ve made sure that the cloth won’t slip.

You’ve made sure that it bounces right,

And that your toes can get a grip—

And you’ve been up there since half past five

Doin’ everything… but DIVE.

45.

HAPPY ENDING? (

Every Thing On It)

There are no happy endings.

Endings are the saddest part,

So just give me a happy middle

And a very happy start.

46.

YEARS FROM NOW (

Every Thing On It)

Although I cannot see your face

As you flip these poems awhile,

Somewhere from some far-off place

I hear you laughing—and I smile.

So that’s what it became—MY MANTELPIECE: A Memoir of Survival and Social Justice.

So that’s what it became—MY MANTELPIECE: A Memoir of Survival and Social Justice.

61.Nerd Do Well (Simon Pegg)

61.Nerd Do Well (Simon Pegg)

_(tilD0031a).jpg)

.jpg)

_cropped.jpg)